|

|

Welcome to;

The Fire Mark Circle

A brief history of Fire Insurance.

|

Before the advent of fire insurance, the only assistance available

to the owner of a property damaged by fire was though a 'Brief' in church.

The parson drew the parishioners' attention each Sunday to specific causes

of want or hardship in the parish in the hope that his flock would help the

needy financially. Naturally, this was totally inadequate in the event of a

large fire, and most of the loss had to be borne by the unfortunate owner

of the damaged property.

|

|

In the reign of Charles II the disasterous losses resulting from the Great

Fire of London in 1666 bought into being the first societies for insurance

against loss or damage of property by fire, and by the end of the

seventeenth century three London societies were actively engaged in the

business: the Fire Office, later known as the Phenix Fire Office,

established in 1680; the Friendly Society, established in 1683; and the

Amicable Contributors for Insuring Loss by Fire, later known as the Hand

in Hand, established in 1696.

|

|

|

A number of new fire insurance companies were established in the early part

of the eighteenth century, most of them having their offices in the London

area. Eight of these survived the scandalous situation that was revealed when

the financial crash of the South Sea Company brought to light many

fraudulent joint-stock companies, some connected with insurance, which

became known as 'bubbles'; this culminated in the Bubble Act of 1720, which

was aimed at preventing the raising of stock capital by means of

transferable shares.

|

|

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the only means of communication

between different parts of Great Britain were stagecoach or horseback. It is

not suprising, therefore, that at first very little fire insurance was

transacted outside the city or town in which a company's office was situated.

As communications improved towards the latter part of the eighteenth century,

the business activities of the fire insurance companies began to spread into

all parts of the British Isles, and new companies were started by local

businessmen in many provincial cities and towns.

|

|

Many of these early fire insurance companies were small concerns depending on

local support for their success; some of the companies were successful and

were able to extend their activities over a greater area, while others,

unable to attract any great measure of support, soon found themselves unable

to continue in business and ceased to operate.

|

|

Before 1800 the naming of streets in our cities and towns was rather

haphazard, and the houses and other buildings in these streets were neither

named nor numbered as they are today. Signs and emblems were used by

traders and inn-keepers to denote their occupation and to draw attention to

their premises, but private houses were not as easy to identify and it was

often difficult for persons who did not live in the immediate vicinity to

locate a particular house.

|

|

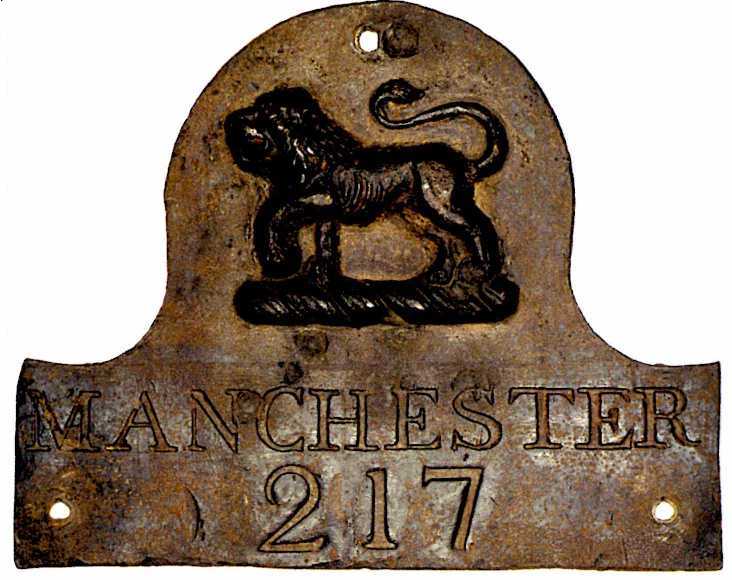

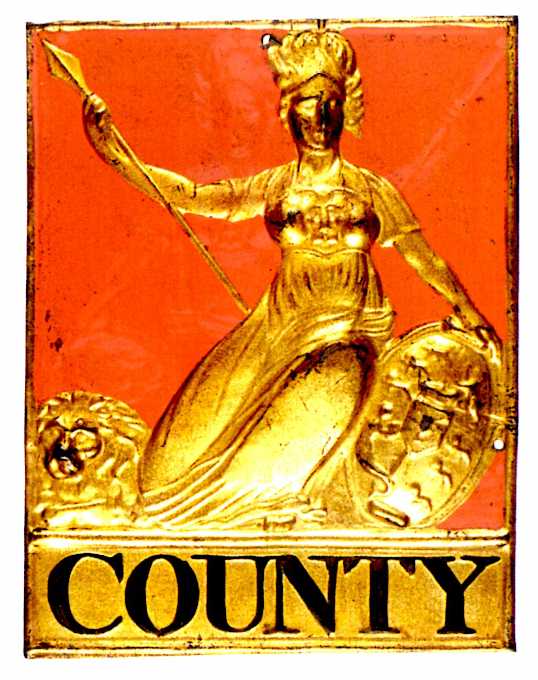

When insuring a property against risk of fire,

it was neccessary that the company's officials and firemen should be able to

identify an insured property immediately, and so it became the practice for

each insurance company to adopt a distinctive emblem for its own use, which

was displayed on metal signs fixed to the wall of each property insured; this

emblem usually appeared at the head of the company's insurance policies and

other documents. Many of these wall marks were made of lead, cast in a mould

and the number of the policy covering the particular property was stamped on

a panel under the design with number dies.

|

|

|

The marks of each company varied in

shape and size, and most were brightly coloured, usually affixed to

the front of the insured building, at such a height from the ground as to be

both easily visible and beyond the reach of pilferers. In the late

eighteenth century there was a sharp rise in the price of lead and the

companies began to use thin sheets of copper and other metals in the

manufacture of their marks, on which the design was pressed out. As

properties became easier to identify, the practice of impressing or

painting the policy number on marks gradually came to an end.

|

|

In the early days of fire insurance, companies made it a practice to remove

their marks from a property when the policy lapsed, and as a result the

marks of some companies, particularly those with early policy numbers on

them, are very scarce. Some small companies issued only a few of their marks

before going into liquidation or being taken over by one of their more

successful rivals. Demolition of properties through the centuries and bomb

destruction during the Second World War also took their toll and have added

to the rarity of these old fire insurance marks.

|

|

When the Great Fire of London broke out in the early hours of the

morning of 2nd September 1666, there were no organised groups of men trained

to fight fires, and such water supplies and fire-fighting equipment as then

existed were totally inadequate to combat such a fire. The weather had been

warm and dry for some weeks and there was a strong east wind blowing; it is

not suprising, therefore, that the fire spread rapidly among the wooden

houses and buildings and along the narrow streets and alleys of Charles II's

London. This devastating fire continued to burn for four days, destroying

over 13,000 houses and many public and private buildings including the

original St. Pauls Cathedral, bringing ruin and misery to many thousands of

London's inhabitants.

|

|

Following a catastophe of this magnitude, men's thoughts were full of

rebuilding both houses and businesses, of making regulations to control both

the construction of buildings and the width of the streets between them, and

of improving fire-fighting equipment and water supplies, in and effort to

prevent such a loss by fire ever happening again. It was in 1680 that the

first fire insurance company (called simply the Fire Office) was established

in London and formed an organised fire brigade to protect the properties

insured with it.

|

|

As the idea of insurance grew and more and more fire

insurance companies were formed, these companies also realised the necessity

of having their own fire brigades, and so it became usual for new fire

insurance companies to form their own fire brigades to put out any fires

that might occur in the properties they insured. The companies soon found it

necessary to have persons under their own control to look after their

interests in cases of fire, instead of being dependent upon casual labour;

this lead to their employing men to act as firemen. In London the insurance

companies recruited most of their firemen from among the free watermen (or

ferrymen) of the river Thames, finding that they were strong, reliable men,

well used to danger, who could always be found at specified places owing to

their calling, and could, therefore, be readily summoned to a fire.

|

|

A company would employ from eight to thirty men for a brigade and some

companies employed additional men as porters to remove goods

from burning buildings or from buildings threatened by fire. In some cases

the foreman, or engineer, was paid a salary, but the ordinary firemen

usually received a retaining fee, and were paid a fixed amount in addition

for each drill or fire that they attended, which gave them a valuable

supplementary source of income to add to their earnings as watermen.

|

|

|

The free watermen, when following their calling, were accustomed to wear

badges on their arms. Noblemen provided their own watermen with their

usual livery, and also gave them a large silver badge to wear upon the

left arm with the nobleman's coat of arms embossed on it. It was therefore

quite natural that the insurance companies should provide their fireman

with a distinctive livery, consisting of caps, coats, breeches, stockings

and shoes, and that they should also provide each fireman with a large

badge to wear upon the upper part of the left sleeve of his coat with the

company's emblem embossed on it. Many of these arm badges were made of

silver and silver-gilt, some of the later badges being made of silver-plated

metal and others of brass. These arm badges were usually numbered from 1

upwards, so that members of the public could easily identify any individual

fireman if it became necessary to do so. The liveries of the different

insurance companies' fire brigades varied widely in colour; and some

companies also provided top hats for their firemen to wear on ceremonial

occasions. Leather caps or helmets were worn when on fire-fighting duty,

and these were usually decorated with the company's name or emblem in

bright colours.

|

|

The insurance companies' fire brigades continued to grow in number. Their

obligation, however was to the insurance company that employed them, and

many of the companies in those days could not afford to pay their fireman

to fight fires in which they were not financially interested, unless they

were indemnified for their expences or received reciprocal assistance in

fighting their own conflagrations. Several attempts were therefore made

by thinking men to bring about some degree of co-operation between

individual companies to assist each other in extinguishing fires, and

eventually in 1826 an agreement was made between the Sun Fire Office,

the Royal Exchange Assurance and the London Assurance and the Phoenix

Fire Office to combine their fire brigades when necessary, to fight fires

under the leadership of one Superintendent.

|

|

This agreement in turn led to increased co-operation between other companies'

fire brigades, culminating in the formation of the London Fire Engine

Establishment on 1st January 1833 by ten of the leading fire insurance

companies, with a committee formed by these companies in general control,

and with Mr James Braidwood from Edinburgh as Superintendent of the

Establishment. The remaining fire insurance companies which had fire

brigades in London eventually joined the Establishment.

|

|

The London Fire

Engine Establishment employed a permanent body of firemen, ready at all

hours to give immediate attendance at fires, and had fire stations in

various parts of London, where there were firemen in attendance twenty-four

hours a day.

Mr Braidwood was killed by a falling wall in the Tooley Street, Bermondsey,

fire in 1861. His death was a great loss to the Establishment, and in 1866

the control of fighting fires in London was handed over to the Metropolitan

Board of Works, subsequently the London County Council.

|

|

|

In the provinces the insurance companies' fire brigades continued to maintain

their own individual fire brigades until well into the second half of the

Victorian era, and some of them continued to operate until the early years

of the twentieth century. These insurance companies' fire brigades were

eventually either disbanded or taken over, one by one, by local city or

town authorities when those bodies decided to form their own fire brigades.

Probably the last survivor of these ancient fire brigades was the Norwich

Union Insurance Society's fire brigade which operated in Worcester until it

was disbanded in March 1929.

|

| Reproduced, with permission, from the book

'The British Fire Mark 1680-1879' by Brian Wright.

|

(All photos this page: R. Addis.)

|